Left-wing activists cling to the idea that there is an inherent anti-Tory majority, if only the opposition parties could get their act together and cooperate. Real election results, though, make it clear that there is no such thing.

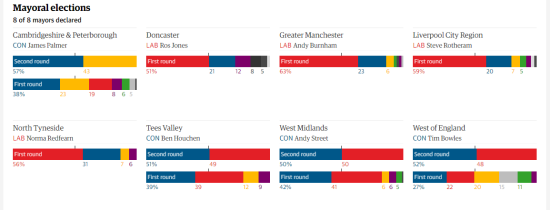

Eight new “metro mayors” were elected this week. What’s interesting about mayoral elections is that they use the supplementary vote system – if no candidate gets more than 50% of the first preferences, the votes cast for all but the top two candidates are reallocated according to their second preferences.

If there is a “progressive alliance” among the electorate, therefore, the way that the second preferences are distributed will reflect this. As it happens, though, they don’t.

Of the eight mayoralties contested, four were won by Labour and four by the Conservatives. The Labour victories were all achieved with more than 50% of first preferences, so second preferences didn’t come into it. But the four Conservative wins all needed second preferences to reach a result.

Image screenshot from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/ng-interactive/2017/may/04/local-and-mayoral-elections-2017-live-results-tracker

In all four of those cases, the total Labour, LibDem and (where applicable) Green vote in the first round was more than 50%. So, if all of the Green and LibDem voters had given Labour their second preferences (or, in Cambridge and Peterborough, Labour voters had given the LibDems their second preference) the Conservative candidate would have been defeated in the second round (even assuming, charitably, that all the Ukip voters made the Tories their second choice).

So, when given the opportunity to vote for a progressive alliance, the electorate didn’t take it. At least some LibDem and/or Green voters must have chosen the Conservatives as their second preference (and, in Cambridge and Peterborough, some Labour voters must have done so too).

This is shown most clearly in the Tees Valley contest, where there were only four candidates and hence the possible interplay of second preferences between different minor parties can effectively be ruled out. In the first round, Labour’s 39% and the LibDem’s 12% add up to 51%, compared with the Conservatives’ 39% and Ukip’s 9% making a total of 48% (numbers don’t add up to precisely 100% due to rounding, before you ask!). But in the second round, the Tories won by 51% to Labour’s 49%. The LibDem voters could have put the Labour candidate into the mayor’s office with their second preferences, had they wanted to. But not enough of them did want to.

Now, I don’t find this at all surprising. It corresponds with a similar analysis of the 2015 general election, for example. But it still seems to be beyond the grasp of those clinging to straws in the hope that the centrist LibDem voters will somehow prefer Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour to Theresa May’s Conservatives.